Rubãƒâ©n Darãƒâo Took His Idea of and Belief in El Arte Por El Arte or ?art for Art?s Sake? From

Should Art take a Purpose?

"Art for art's sake is an empty phrase. Art for the sake of truth, fine art for the sake of the good and the beautiful, that is the faith I am searching for (Ratcliffe, 2011, p.29)." This phrase from Victorian author George Sand was a response to the trend in the romantic era to celebrate fine art that does non accept or need a purpose. It is a rendering in English of l'fine art pour l'fine art, a phrase coined by philosopher Victor Cousin (Encyclopædia Britannica, 1999). This thought continued well into the 20th century and became the basis for ceremonial, although in recent years the belief that fine art must have a purpose and an artist must justify what they do has become prevalent. And then does art really need a purpose, and what exactly practice nosotros mean by purpose?

To empathize this idea one must go dorsum prior to the 1800s, when artists were non costless as such and required patronage by wealthy people to produce artworks that were specifically commissioned. Art in those days was created specifically to serve a function. A lot of artworks were religious in nature as the virtually bachelor commissions were the decoration of churches (Bohn & Saslow, 2012, p.65).

Portraits of of import people were too existence produced, as they were another common commission. These were often heavily embellished to make the subject area appear more powerful, or bonny that they actually were, leading sometimes to blatant fabrication of details. Jacques-Louis David'due south Bonaparte Crossing the Grand Saint-Bernard Laissez passer (Effigy 1) is a good example of this.

Napoleon is pictured leading his troops beyond the Alps astride a bucking horse. Unperturbed, he confidently points the way. In reality, he did non lead his troops beyond the Alps but followed them up the side by side twenty-four hour period on a ass. He also never posed for the painting. David used a sketch of his head and modelled the trunk on that of his son climbing a ladder (Cunningham et al., 2016, p.640).

By the 1800s artists started to adopt a new paradigm of beingness independent and figures of greatness. Photography would somewhen make mere reproduction easier and freed art to be more expressive, and the ascension of industry led to the arrival of the Romantic Move, which was characterised by a deepened appreciation of the beauty of nature and an adoration of emotion over reason and intellect (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019).

Walter Pater, 1 of the foremost fine art critics of the era, disseminated the belief that fine art should provide sensual pleasure rather than convey a meaning or bulletin, an ideology that inspired painters like Whistler and even writers such as Oscar Wilde (Nunokawa & Sickels, 2005, p.5). He wrote in the conclusion of his almost successful book The Renaissance, that "To burn always with this difficult, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life" (Pater, 1928, p.221), an idea he developed further in the aptly-named Marius the Epicurean. He goes on to push "the love of art for its own sake" (Pater, 1928, p.223).

In contrast to Pater's view, John Ruskin and later advocates of socialist realism believed that art should serve a moral or didactic purpose. Ruskin declared that "the entire vitality of art depends upon its existence either full of truth, or total of use" (Ruskin, 1996, p.140).

Caspar David Friedrich was a painter of the Romantic Movement and, Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer (The Wanderer above the bounding main fog) (Figure 2), is one of his all-time-known works. It displays a young man with a walking stick shown from behind, standing on a rocky precipice looking out across a rough body of water. In the far distance, there is a faint appearance of mountains and the fog and clouds seem to blend. Equally the man's face cannot exist seen, it is impossible to know whether his experience is "exhilarating, or terrifying, or both" (Gaddis, 2004, p.1).

Friedrich once said "the artist's feeling is his law" (Wiedmann, 1986, p.46). This quotation is rather apt as he really captures the raw power and beauty of nature and the feeling of the individual in the midst of it in this work.

Towards the finish of the Victorian era, a less optimistic, more honest and raw art motility appeared. Expressionism featured harsh colours, jagged edges, more vehement brushwork and nighttime field of study matter. Influenced by Friedrich (Gariff et al., 2008, p.140), Edvard Munch was a key figure of this movement.

Munch's life was tortuous at best. His mother died from tuberculous during his fifth Christmas, he caught it seven years after and eventually watched his sister die from it (Høifødt, 2012, p.seven). In Munch'south own words, "The illness followed me all through my childhood and youth — the germ of consumption placed its claret-red banner victoriously on the white handkerchief" (Prideaux, 2005, p.66).

Det syke barn (The Sick Child) (Figure iii), is a portrait of Munch's sis Sophie made a decade later. He used a daughter called Betzy Nielsen, described every bit "consumptively beautiful with a blue-white skin turning yellow in the blue shadows" equally a model for his dying sis in the painting. Described as "consumptively beautiful with a bluish-white skin turning yellow in the bluish shadows". He proceeded to pigment her while sitting in the wicker chair in which Sophie had died (Prideaux, 2005, p.86).

In this painting and many of Munch's subsequent renditions of it, a frail girl is seen propped upwardly in bed. Her caput is turned to face up an older woman who is holding her hand and hanging her head in profound sadness. I can feel a strong sense of anticipatory grief from the older woman at the thought of losing the child, who conversely appears to have accustomed her fate. In the girl's path of sight is a long dark curtain which could be interpreted as a symbol of her imminent death. This painting was referred to as his first sjælemaleri, or "soul paintings" (Prideaux, 2005, p.84).

Munch one time said "I paint not what I meet but what I saw" (Høifødt, 2012, p.7). Much similar Friedrich, Munch's feeling was his law and he used painting as a way to resolve troubling past events in his life like his sister's expiry.

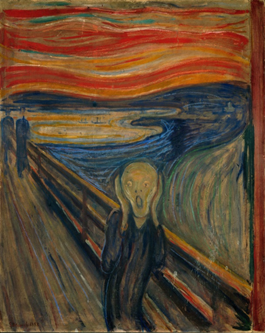

Information technology was also certainly true of his most famous work, Skrik (The Scream) (Figure iv), which was inspired by a memorable evening when he was walking with friends during a sunset. The heaven turned "blood red", and "Trembling with anxiety" he "sensed an infinite scream passing through nature" (Lowis, 2009, p.119).

This painting features a distraught white figure, its hands raised to concord its face, screaming with large open eyes. There is an unforgettably ghastly expression on the face of the individual, who represents Munch during his experience of the dusk.

Through a post-mod lens the approach of the expressionism been criticised for its "very hermeneutic model of the inside and the outside" (Harrison & Wood, 2002, p.1049). Theorist Fredric Jameson, in a text about "the waning of bear upon in postmodern civilization" said of The Scream, it "deconstructs its own aesthetic of expression, all the while remaining imprisoned within it." (Harrison & Woods, 2002, p.1050).

It would announced that every bit art for art's sake waned in the 20th century, audiences became more discerning. He goes on to say, "concepts such as anxiety and alienation (and the experiences to which they correspond, as in The Scream) are no longer appropriate in the world of the postmodern". The purpose behind this painting is no longer relevant, as it is self-indulgent. Information technology must be more accessible by others, according to theorists like Jameson.

Emil Nolde, some other expressionist artist perhaps as well influenced by Friedrich (Schmied, 1995, p.forty), carried on the expressionistic style of painting into the 20th century. Meer (I) (Figure 5), or Bounding main in English, is one of his works produced before long subsequently the Second World War ended.

Nolde was banned from making art by the Nazis, and had more of his works confiscated than any other artist, on the basis that his work was "degenerate" (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2019). Yet he was a member of the Nazi political party, and remained a supporter until the end of the war.

This piece of work features a claret red sky traversed by thick black clouds. Below information technology is a restless sea painted in blueish and green shades. Information technology seems very advisable for an immediate post-war expressionist painting. Mayhap, the red heaven with blackness clouds signifies an anger or fear apropos the finish of the war. The restlessness of the ocean may represent the restless feelings of Nolde, who had lost his married woman Ada to a centre attack the previous twelvemonth. He in fact painted many images of the sea due a memorable crossing of the Kattegat strait in a fierce tempest in 1910 (Selz, 1963, p.72).

Despite his ban from painting, he still managed to quietly paint many watercolours during the state of war which he referred to every bit "Unpainted Pictures" (Selz, 1963, p.lxx). Perchance the need to express his cocky was as well corking for even the Nazis to totally prevent. The purpose of his art is similar to Friedrich's, in that he painted many seascapes and landscapes because he felt a need to paint them. Those things held significance for him, in much the manner Munch's sister's decease was significant to him.

Moving on to the 60s, fine art was becoming yet more than abstruse. Pop fine art was at its height but at that place were also many advanced artists such as Advertizing Reinhardt producing works that question how far the boundaries of fine art could be pushed. This pushing of boundaries was nothing new. In the 1910s artists like Marcel Duchamp were doing precisely that. His infamous Fountain, an inverted urinal inscribed with "R. Mutt" in indelible marker, was refused entry and considered not a work of art due its association with actual waste past the Club of Independent Artists (Howarth, 2015).

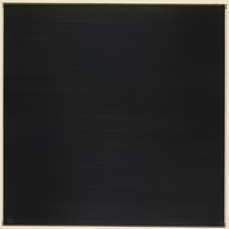

Reinhardt's Abstract Print (Figure 6) is an almost entirely black screen print with a faint white mixed in. The image might be seen by theorists similar Pater as lacking in aesthetic quality but may accept also been viewed as lacking in social purpose by Ruskin. This new grade of art that started with the Dadaists goes beyond painting enigmatic landscapes and edgy screaming figures. It is an attempt to push boundaries of art equally a medium.

One of the problems with "art for art's sake" is the tendency for the fine art market to prosper heavily from these e'er irresolute styles or fashions in art, which are just stylistic and challenge nada. Creative person and writer Ian Burn believed that this helped to prop upwards capitalism, especially in 1970's New York (Harrison & Wood, 2002, p.936). Artists like Salvador Dalí, whose dream-like imagery and style accept go very well-known, is an artist that the art market conspicuously loves, every bit his Portrait de Paul Éluard sold for near £13.v meg in 2011 (Sotheby's, 2011). Yet the work is adored its style not for its meaning.

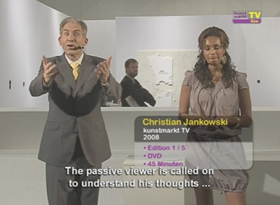

Burn down'southward argument is based partly on the ideas of theorists similar Ruskin, that art should be used for the social good, which has go a prevalent in the modern era. A lot of artists focus on social or political problems, and those that produce works that do not challenge anything, peculiarly in a troubled land are sometimes seen as upholding the condition quo. Artist Christian Jankowski produced a live stream called Kunstmarkt Telly (Figure seven), or Art Marketplace TV in English language, which features two presenters that sell artworks in the style of a teleshopping Tv station (Frost, 2013). This was his way of critiquing the art marketplace and how it undermines the social value of such art.

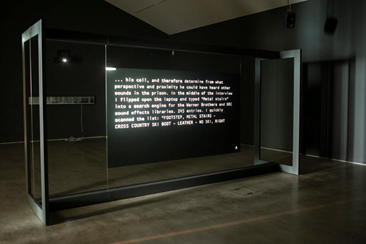

Lawrence Abu Hamda'due south Afterwards SFX (Figure 8) is a work that is certainly uniform with Ruskin's view of Art. It is based in a large dark room with a prepare of speakers that surround the viewer playing eerie noises, while a large screen displays text explaining that the sounds are those heard by prisoners in a Syrian regime prison.

Hamda is an audio investigator for Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture and this work represents crimes that are heard but non seen (Tate, 2019). Information technology seeks to inform the audience of the critical work done by sound investigators Like Hamda while immersing the audience into the frightening experience of the prisoners, which emphasises the urgency of his work. This would be seen by writer Marshall McLuhan as the creative person fulfilling their duty by provoking discussions and forcing people to appoint with real globe issues (Harrison & Wood, 2002, p.756).

Proponents of aestheticism in the 19th century like James McNeil Whistler however, would view the work as confounded by "claptrap" (Sutherland, 2014, p.155), and politically and emotionally loaded. To produce that deals with socio-political themes and is quite directly linking to existent world events is to an extent a modern concept, and one that is influenced much by proponents of art with a social purpose, like Ruskin.

From the analyses of the artworks, i can deduce that the older works by Friedrich, Munch, and Nolde, are well-nigh expression of emotions, resolving of traumatic events and painting for pleasance. Their work serves the needs of the artists and may be seen by some every bit cocky-indulgent. Artist Mel Ramsden once complained of "indulgent individual freedom" in artistic practices in 1970s New York. These "insular and slow" fads that he complained of, were examples of artistic liberty that, as Ian Burn feared, were subservient to the fine art market (Harrison & Forest, 2002, p.933).

In the case of Duchamp and Reinhardt, their work is very abstruse and is intended to challenge what tin can be considered art. Both proponents of aestheticism and socio-political fine art would perhaps dislike this art even though it has a clear purpose.

For afterward artists like Jankowski and Hamda, the work serves to raise awareness of issues in the world and bring attention to the necessity for socio-political change. Theorists similar Ruskin and McLuhan would have approved of Hamda's work, as it theoretically improves order by promoting sensation of social problems.

My own work varies from mere abstract or symbolic expressions of my feelings, similar the expressionists, to humorous demonstrations of socio-political issues via exaggeration, like Jankowski. The German language concept of Weltschmerz, a lamenting of the human condition, prominently features in my work, heavily influenced past philosophers Schopenhauer, Wittgenstein and Kierkegaard, and the artists Munch and Nolde.

This view that art should exist cute or produced entirely without a specific purpose is seen equally wasteful in the modern era but in reality it could exist just as valid as the philosophy of Ruskin that art should serve a social purpose. Friedrich believed that "nada is incidental in a picture" (Friedenthal, 1963, p.33), and Nolde said similarly that the "soul of the painter lives inside" paintings (Miesel, 2003, p.37). Both of these phrases are a way of saying the aforementioned thing, that any creative person will get out parts of their identity in their work, even if completely unintentionally. By this logic, all art automatically expresses the artist's identity and feelings, and therefore has a purpose from the showtime, even if it is not the artist's intention. This renders the main question being investigated somewhat invalid, every bit perhaps the question should be which purpose is best for Art.

Fifty-fifty if fine art is used past some artists every bit a form of self-therapy, it is even so a valid purpose, and no doubt there are many other people that have shared or like life experiences to artists like Munch or Nolde, and therefore the work may strike a chord with them. Sometimes art has to be self-indulgent in order to project the very circuitous and specific feelings that an private might have, and those of a similar disposition may find that work much stronger than work portraying a more political or social issue. This quickly becomes an argument well-nigh minorities versus majorities, and whether or non the individual is most important or large social groups.

Much of this debate rests on the definition of purpose. If we consider purpose to be the ultimate effect on the viewer, regardless of the artist's intentions, and then art could be considered to accept absolutely no purpose past some and exceedingly purposeful past others. If we consider purpose to be the artist'due south reason for creating the work, whatever that motivation might exist, past that definition any artwork will automatically accept purpose. Fifty-fifty if it is merely to bring pleasure, information technology is notwithstanding fulfilling a primal human need.

Whatever the purpose or part of art, it is also necessary to define Art. The latter definition of purpose would appear to mark everything one tin can create as a work of art, even if it is the carbon dioxide we breathe out. This is somewhat reminiscent of Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys' view that everyone is an artist (Harrison & Woods, 2002, p.905).

Revisiting the Victorian era, Ruskin believed that art and civilisation could become a replacement for faith after increasing secularisation was inevitable (Cheeke, 2016, p.24). Indeed art theorist André Malraux believed that this has already happened. In Les voix du silence (The Voices of Silence), he said that "modernistic masters paint their pictures as the artists of ancient civilisations carved or painted gods" (Malraux, 1974, p.616). The agenda for Art delineated in Art equally Therapy past philosopher Alain de Botton and fine art history John Armstrong, is that art should "assist mankind in its search for cocky-understanding, empathy, consolation, hope, self-acceptance and fulfilment" (de Botton & Armstrong, 2019, p.230).

Ultimately fine art has get a new faith, and while there is certainly room for aesthetic dazzler and intriguing imagery, there is likewise a firmly established civilization of art providing socio-political commentary. Information technology is mayhap not surprising that in a war-torn country, for instance, an artist might exist seen as a sell-out for producing fine art that is beautiful, however in a successful country, it may exist a bit more acceptable. Fine art reflects greatly the time and location in which it was produced, and adapts to the needs of different societies, so the all-time purpose for art is subjective therefore it seems myopic to restrict what art should be.

As discussed earlier, any art will have a purpose by the latter definition, and following the commencement, only certain pieces would accept a purpose. Is this just arguing over semantics and groups arguing by each other? Wittgenstein said that "if a panthera leo could speak, nosotros could non understand him" (Hofstadter, 1980). That is because the lion'due south culture is so vastly different to ours that, even if we understood the words, they will not hateful the same affair as in our language. Perhaps the existent purpose of art should be to mind to the proverbial panthera leo, forgetting about the words and grammar, and take its vocalisations equally ane of many valid commentaries on life.

Bibliography

a-n, 2019. Lawrence-Abu-Hamdan-After-SFX-2018.-Turner-Prize-2019-at-Turner-Contemporary-Margate-2019.-Photo-past-Stuart-Leech-2 — a-n The Artists Information Company. [Online] Available at: https://www.a-n.co.great britain/media/52568843/ [Accessed 29 November 2019].

Cocked, 2018. Caspar David Friedrich | Wanderer above the Ocean of Fog (ca. 1817) | Artsy. [Online] Available at: https://www.cocked.internet/artwork/caspar-david-friedrich-wanderer-above-the-sea-of-fog [Accessed eighteen November 2018].

Artsy, 2018. Edvard Munch | The Scream (1893) | Artsy. [Online] Bachelor at: https://www.artsy.net/artwork/edvard-munch-the-scream [Accessed xviii November 2018].

Bohn, B. & Saslow, J.M., 2012. A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Cheeke, Due south., 2016. Transfiguration: The Religion of Art in Nineteenth-century Literature Before Aestheticism. Oxford: Oxford University Printing.

Cunningham, L.S., Reich, J.J. & Fichner-Rathus, L., 2016. Culture and Values: A Survey of the Humanities, Book 2. Boston: Cengage Learning.

de Botton, A. & Armstrong, J., 2019. Art as Therapy. London: Phaidon.

Dewald, J., 2004. Europe 1450 to 1789: Absolutism to Coligny. New York: Charles Scribner'southward Sons.

Encyclopædia Britannica, 1999. Encyclopedia Britannica | Britannica.com. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/art-for-arts-sake [Accessed 01 November 2019].

Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019. Romanticism | Britannica. [Online] Available at: https://world wide web.britannica.com/fine art/Romanticism [Accessed 28 November 2019].

Friedenthal, R., 1963. Letters of the Great Artists: From Blake to Pollock. New York: Random House.

Frost, A., 2013. Art takes on capitalism: merely what'due south at stake? | Art and design | The Guardian. [Online] Bachelor at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/australia-culture-blog/2013/aug/28/art-capitalism-fiscal-report [Accessed 10 Dec 2019].

Gaddis, J.L., 2004. The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garbrecht, J., 2008. Emil Nolde: Mein Wunderland von Meer zu Meer (My Wonderland from Sea to Sea). In M. Reuther, ed. Emil Nolde: Mein Wunderland von Meer zu Meer (My Wonderland from Sea to Sea). Köln: DuMont. pp.17–43.

Gariff, D., Denker, E. & Weller, D.P., 2008. The world's nigh influential painters and the artists they inspired. London: A & C Blackness.

Google Art Project, 2019. Bonaparte Crossing the Grand Saint-Bernard Pass, xx May 1800 — Jacques Louis David — Google Arts & Culture. [Online] Available at: https://artsandculture.google.com/nugget/QwEFHqZhgW6ulw [Accessed 29 November 2019].

Harrison, C. & Woods, P.J., 2002. Fine art in Theory 1900–2000. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hofstadter, D.R., 1980. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Gilt Complect. London: Penguin.

Høifødt, F., 2012. Edvard Munch. London: Tate.

Howarth, S., 2015. 'Fountain', Marcel Duchamp, 1917, replica 1964 | Tate. [Online] Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/fine art/artworks/duchamp-fountain-t07573 [Accessed 25 March 2018].

Jankowski, C., 2008. Kunstmarkt TV / Art Market Television set — Christian Jankowski. [Online] Available at: https://christianjankowski.com/works/2008-2/kunstmarkt-television-art-market-tv/ [Accessed 12 December 2019].

Lowis, K., 2009. 50 Paintings Yous Should Know. Munich: Prestel.

Malraux, A., 1974. The Voices of Silence. Translated past S. Gilbert. St Albans: Paladin.

Miesel, Five.H., 2003. Voices of German Expressionism. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

MoMA, 2019. Ad Reinhardt. Abstract Impress from New York International. 1966 | MoMA. [Online] Bachelor at: https://www.moma.org/drove/works/65825?association=portfolios&locale=en&folio=i&parent_id=65817&sov_referrer=association [Accessed 14 December 2019].

Nasjonalmuseet, 2015. Edvard Munch, Det syke barn — Nasjonalmuseet — Samlingen. [Online] Bachelor at: http://samling.nasjonalmuseet.no/no/object/NG.M.00839 [Accessed 27 November 2019].

Nunokawa, J. & Sickels, A., 2005. Oscar Wilde. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers.

Pater, W., 1928. The Renaissance: Studies In The Art And Poetry. London: Jonathan Cape.

Prideaux, S., 2005. Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream. New Haven: Yale Academy Printing.

Ratcliffe, S., 2011. Oxford Treasury of Sayings and Quotations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ruskin, J., 1996. Lectures on Art. New York: Allworth Printing.

Schmied, W., 1995. Caspar David Friedrich. New York: H.N. Abrams.

Selz, P.H., 1963. Emil Nolde. New York: Doubleday.

Sotheby'south, 2011. dalí, salvado ||| impressionist & modern art ||| sotheby's l11001lot5xjx9en. [Online] Bachelor at: http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2011/looking-closely-l11001/lot.7.html [Accessed 11 December 2019].

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2019. Emil Nolde. A German Legend. The Artist during the Nazi Regime. [Online] Available at: https://world wide web.smb.museum/en/exhibitions/detail/emil-nolde-a-german-legend-the-creative person-during-the-nazi-government.html [Accessed 25 November 2019].

Sutherland, D.East., 2014. Whistler: A Life for Art's Sake. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tate, 2019. Lawrence Abu Hamdan: After SFX — Performance at Tate Mod | Tate. [Online] Bachelor at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/performance/lawrence-abu-hamdan-subsequently-sfx [Accessed 1 November 2019].

Wiedmann, A.K., 1986. Romantic Art Theories. Newport: Gresham Books.

Source: https://medium.com/@susanday_25940/an-analysis-of-the-function-of-art-and-whether-it-should-have-a-purpose-6a8b14571479

0 Response to "Rubãƒâ©n Darãƒâo Took His Idea of and Belief in El Arte Por El Arte or ?art for Art?s Sake? From"

Post a Comment